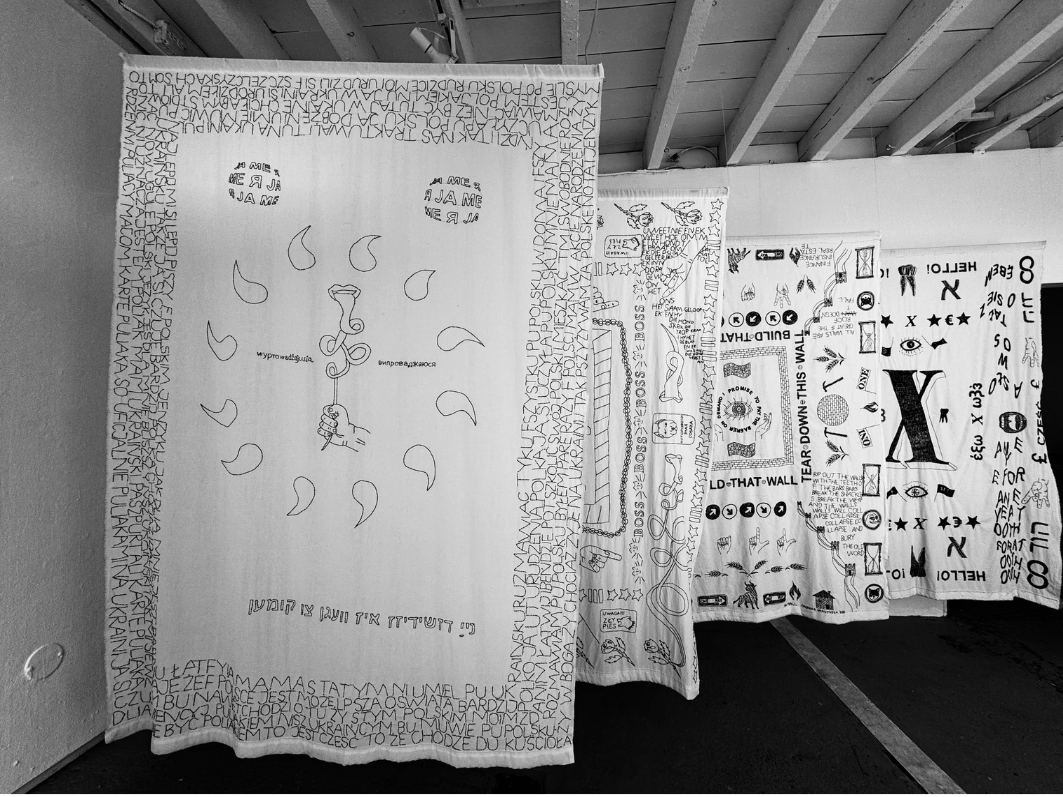

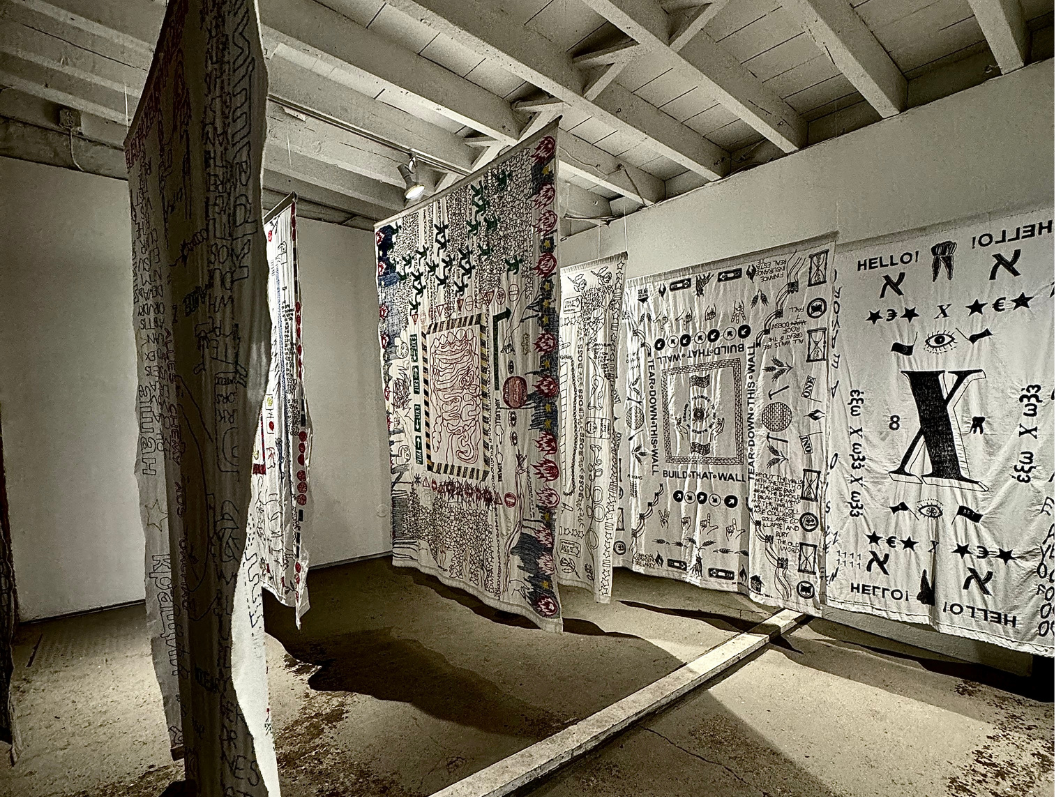

Latte capitalizm

Open Source Gallery, NYC

Curator: Monika Wuhrer, author of the text: Katarzyna Piskorz

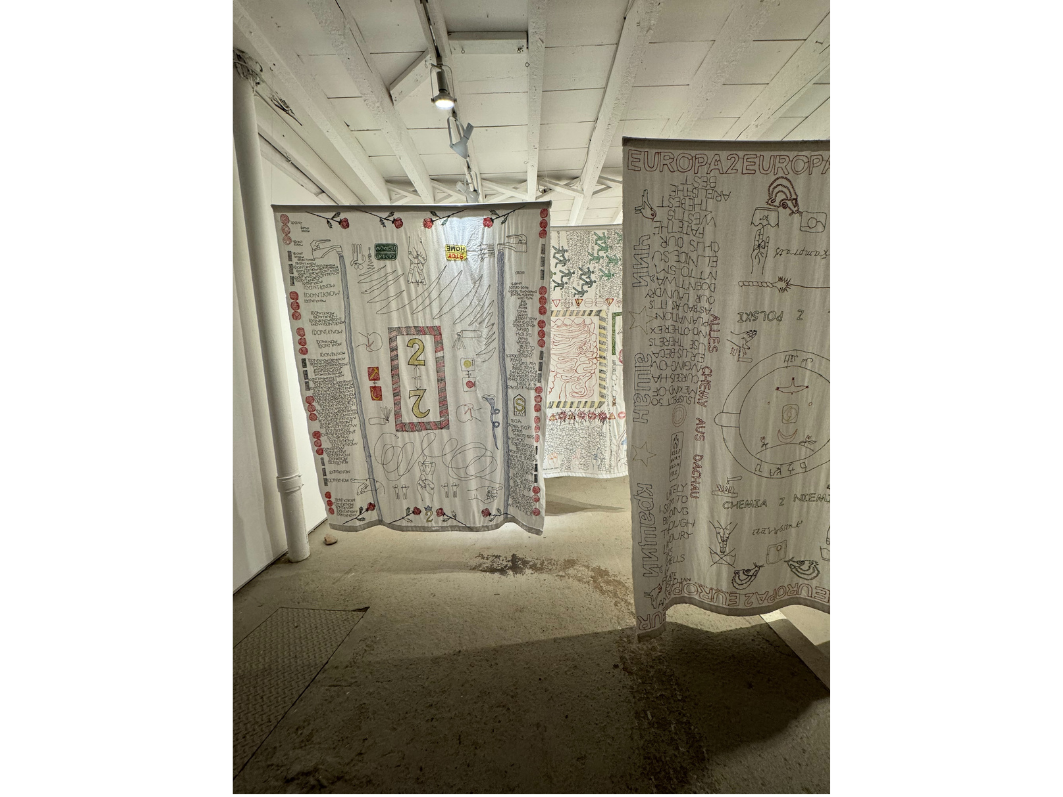

In Drożyńska’s work, the unfolding tale of destruction brought on by expanding capitalism and increasing consumerism is told from a Central European perspective (Poles are reluctant to describe themselves as Eastern European). Her chosen spelling of “Late Capitalism”, with a double consonant (“tt”) and the letter “z” instead of “s” [“Latte Capitalizm”] can be read as a deliberate use of “broken English” and a reminder that being able to speak English in this part of Europe (and many other parts of the world) is still very much a privilege.

The interplay of the two words tells the story of a system fuelled by coffee, which is now undergoing a period of transformation: from a period of imperialist competition for global markets and the ongoing process of automation of production, to a phase of late stage capitalism with all its “benefits” in the shape of established, multinational corporations, the glorification of work, an increasing number of conflicts and crises, widespread injustice, exploitation, and absurdity.

A latte, preferably prepared with lactose-free or plant-based milk. On the go, on the run, in a takeaway cup adorned with an image of a green, two-tailed siren. Latte’ a little for flavour, and a little to stimulate. Coffee is supposed to put you back on your feet, and givee you energy when you’ve run out of it.

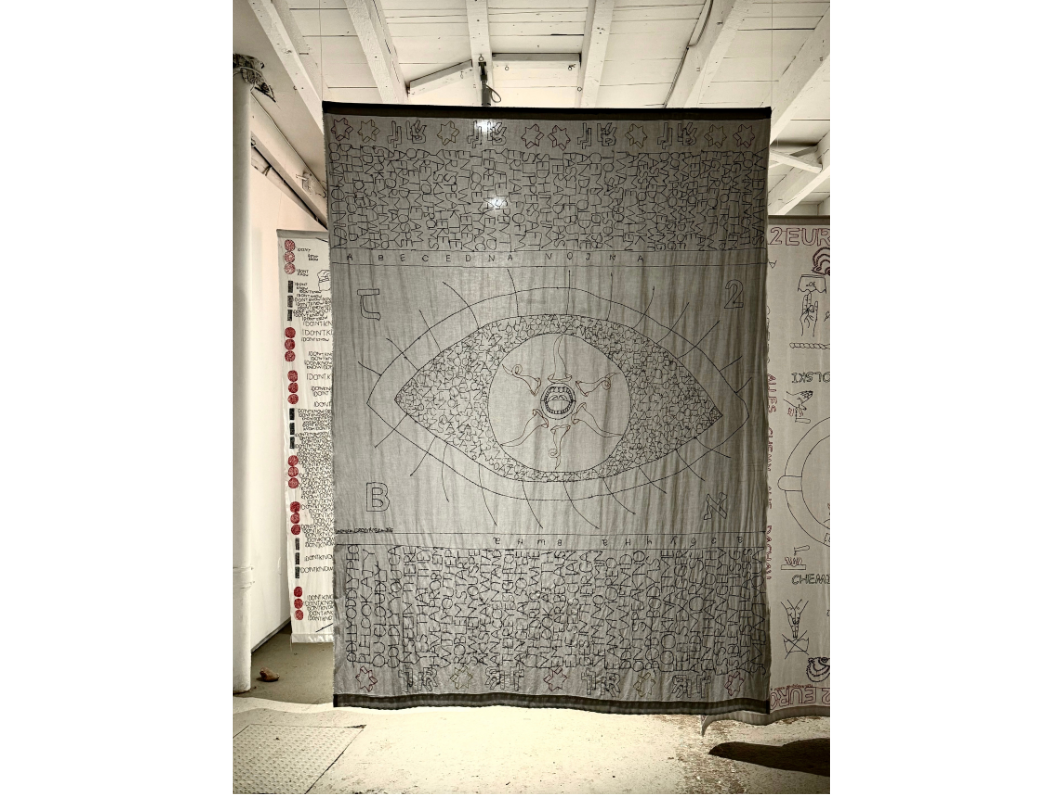

The additional “t” in the first word of the title renders the English word “late” into the Italian word meaning “milk” and brings our attention to themes related to the identity-building role of language. Drożyńska was inspired by the personal story of one of the protagonists of Beata Szady’s book Wieczny początek. Warmia i Mazury [Eternal Beginnings. Warmia and Mazury], Herbert Sobottka. The Sobottka family spoke German at home, and Herbert’s parents and grandparents knew the Masurian language, with its mixture of Kurpie dialect, Old Polish, and German overtones. Following the war, Herbert decided to remain in his “little homeland,” but believed that: “the Yalta agreements on redrawing borders are illegitimate […] this land should remain German, because borders cannot be redrawn. In light of circulating rumours, in order to conceal his German roots from Soviet soldiers, Herbert dropped his middle name, Paul, and the extra “t” from his surname. The Soviets were said to associate the latter (double letters) with aristocratic origins.

Today, we know that the use of a double consonant in the surname was characteristic of German surnames. As such, it had nothing to do with belonging to the aristocracy, whose status was denoted by a lower case preposition preceding the family name, such as von or de. After the war, school certificates showed various variations of Sobottka’s name, such as ‘Sotobotka’, ‘Sobótka’ and ‘Sobotko’. The double ‘t’ disappeared, even though it was always silent, having been absorbed into the Polish spelling.

Finally, we can discuss the deliberate replacement of the letter “s” with the last letter of the alphabet, the Latin letter “z”, which does not have a counterpart in the Cyrillic alphabet. Meanwhile, a letter resembling the Arabic number 3 (Russian: З з), which represents the “z” sound in the Russian alphabet, has become the official symbol of support for the invasion of Ukraine by pro-Russian and far-right groups. This symbol was painted on Russian military vehicles even before the active phase of the war began, and over time it became a key element of Russian visual propaganda. The Russian defence ministry has refused to comment on any of the theories regarding its meaning or the significance of painting it on military equipment. Still, the ministry has begun to post Instagram content in which the “Z” has been incorporated into slogans such as Za pobedu (“For victory”), Zakanhivaem voiny (“We end wars”) or Za mir (“For peace”). The letter “z” also began to appear on clothing distributed by the Kremlin-funded RT network, on buildings and billboards, on gymnast Ivan Kuliak’s shirt during the Doha Gymnastics World Cup competition, lapel pins worn by government officials, banners, and during seemingly spontaneous flash mobs.

In the course of creating this work, Drożyńska coined the term to describe the next phase of capitalism. “Latte Capitalizm” reflects on the marriage between capitalism and war conflicts and arms businesses. As consumers who observe all the dramatic events reverberating through the world on platforms such as Instagram and TikTok, we are of course caught up in all of this. This perception is also accompanied by the experience of another, albeit less polarized, iteration of the Cold War. Once again, the nuclear superpowers have taken opposing sides and now seem less and less likely to agree on amicable solutions, let alone compromises or concessions – the historic discipline of the old Cold War seems to be fading.

So, what do coffee, capitalism, the dispute over the spelling of a German surname, and war propaganda have in common? The discipline and the control over an individual. In his Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, Ludwig Wittgenstein wrote: “The limits of my language mean the limits of my world.” To dehumanise language, to eradicate regionalisms, to sever them from their roots and censor them, is to strip away the breadth of perspective, erode the integrity of an individual’s cognitive tools and deprive individuals of one of the last strongholds of rebellion and freedom. Drożyńska’s hand-embroidered works are a thus a call to action: finding one’s voice and being able to speak out should never be taken for granted.